HoloBaby™ Simulation Framework

MaineHealth + the Interactive Commons

"You go into pediatric medicine because you want to improve the outcomes for children, pure and simple. If we can improve a provider's comfort and ability with resuscitation — that will lead to better outcomes for children across Maine, across the US, and across the world."

MICHAEL FERGUSON, MD

NEONATAL MEDICINE

MAINEHEALTH

Photo: Black Fly Media

"That very first prototype absolutely blew me away. It is so engaging. I hadn't expected that part — the visceral engagement. When that prototype baby cries, people go, “Ohhh,” and reach for the baby. That doesn't happen on the classic manikins. There is a realism aspect to this that is not found anywhere else."

MICHAEL FERGUSON, MD

NEONATAL MEDICINE

MAINEHEALTH

“If you don’t regularly employ these complex therapeutic methods, it’s going to be difficult to use the skills when the time comes."

Mary Ottolini, MD, MPH, MEd

George W. Hallett MD Chair of Pediatrics and Professor of Pediatrics at Tuft’s University School of Medicine

HOLOBABY™ MEDIA

INTERVIEW WITH

MICHAEL FERGUSON, MD

How did you get started with this project?

MICHAEL: The need is out there for simulation in areas that don't have simulation labs. We know that simulation training in high-risk and low-frequency situations helps outcomes. That's why you learn how to do CPR so that when it happens, which isn’t often, you know what to do. We're in Maine, which is a big geographical state but a small state by population. Outside of the cities, it gets very rural very fast, and those rural hospitals in Maine have a much higher incidence of poor neurological outcomes from poorly done neonatal resuscitation. That's because things are going to be done poorly in places where they're not practiced.

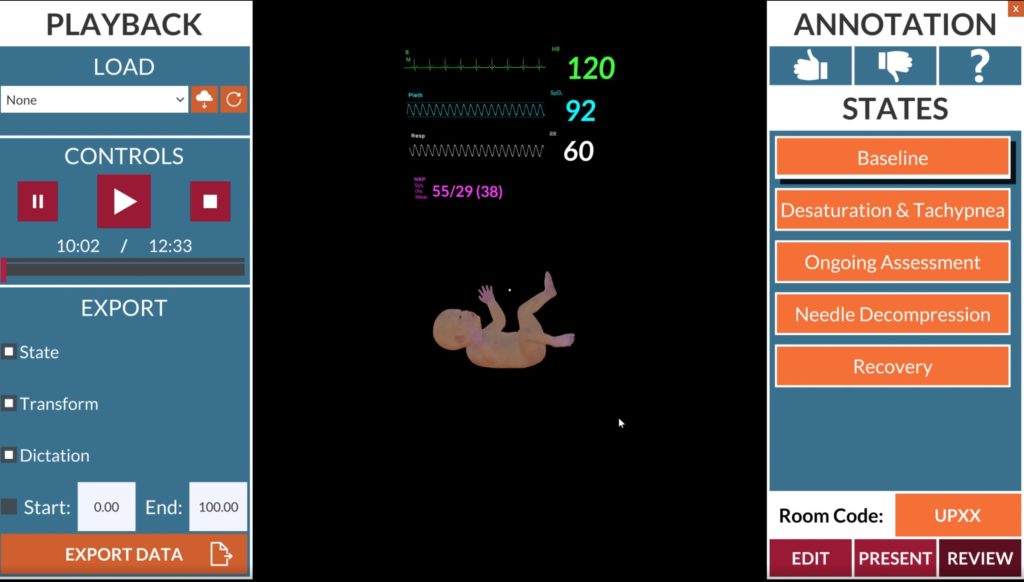

Simulation is the way to practice a rare outcome, but a quick price check on an entry-level simulation lab is realistically about a million dollars — you need a room, a computer, and a few manikins to get the program up and running with people to run it. Any rural hospital can’t afford that, but what if we could design something for $15-20K? Not to necessarily replace high-fidelity simulation, but putting this in a place that has zero simulation, which is probably 80% of hospitals in the country and probably 95% worldwide. So the opportunity is massive, and we knew something high-quality hadn’t been developed yet.

How did you connect with the IC?

MICHAEL: Funnily enough, I borrowed a HoloLens and one of my favorite apps to play with was HoloAnatomy. I loved it, and I actually used it to show the Innovation Team at MaineHealth what could be done without having any connection to Mark [Griswold] or Erin [Henninger]. Then we got a grant and we pulled together some philanthropy money, and there was someone who knew someone who knew Mark. When we met they seemed to like the idea, so we financed the Interactive Commons to develop a prototype. That very first prototype absolutely blew me away. It is so engaging. I hadn't expected that part — the visceral engagement — and that’s

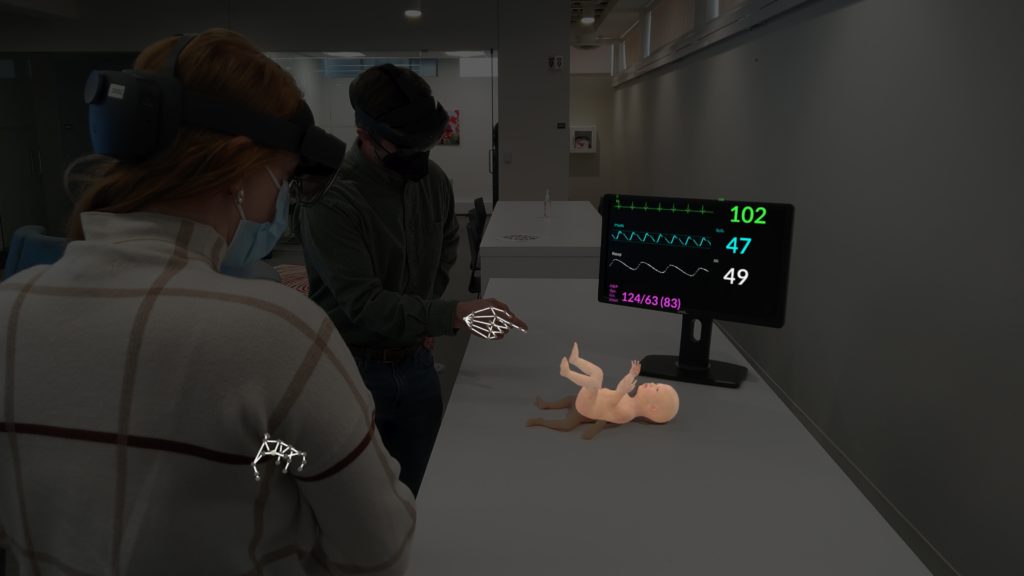

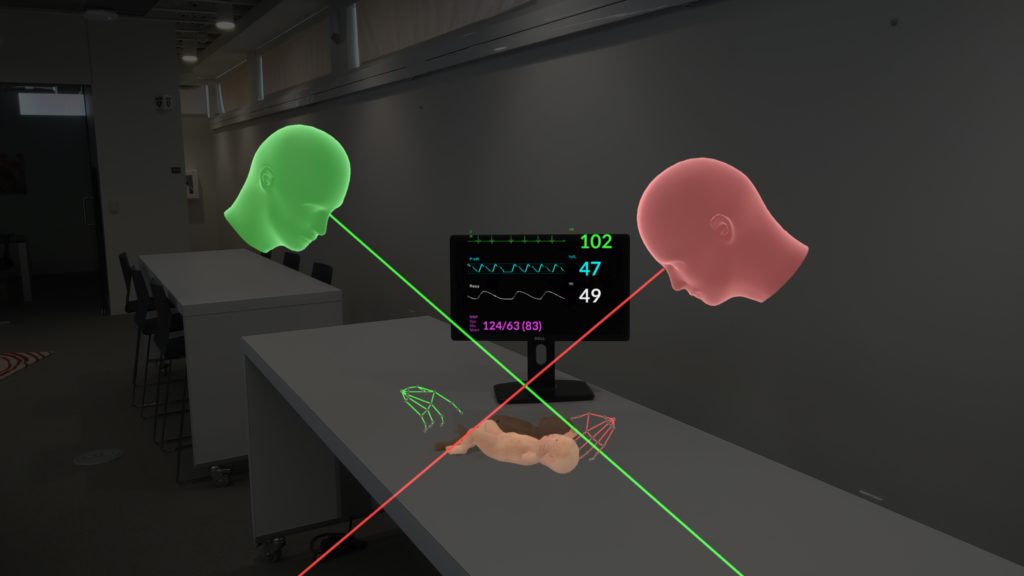

the real power of it. When that prototype baby cries, people go, “Ohhh,” and reach for the baby. That doesn't happen on the classic manikins. There is a realism aspect to this that is not found anywhere else. Also, this simulation happens where you work — you don’t go to a sim lab, or put on virtual reality glasses and go to a foreign space. You're in your delivery room at your hospital where you work every single day, and the equipment you're using is the same equipment you have to reach for with a real baby. The realism of going through the motions in your own environment is way more powerful than going through a fake version in a fake setup sim lab.

When did you know this was really going to work?

MICHAEL: It was actually the first time I showed it. Because I’d imagined it in my head and played with it myself, I didn't realize how incredible it was until I started showing it to people who had never done it before. Specifically, the Innovation group and the cameraman for our video. He put his camera down and he was like, “Whoa! Whoa!” That moment when you reach down and touch the chest, and your finger touches the plastic of the manikin and you can hear the heartbeat in the app and see the baby moving. It really is an amazing feeling.

I have lots of crazy ideas but this is the first one that came into reality. When it was just the idea phase, I floated the concept to some experts in the medical virtual reality world. They very clearly said, “It's not ready. It won't work. It's probably ten years too early.” That was crushing because someone's got to do it! Then in January [2022] at the IMSH Conference in LA, I was at a lecture and they talked about mixed reality coming into play, and that the overlay onto a manikin was the “holy grail” of mixed reality simulation. I sat there thinking, “Um, we’re there. We’ve got it!”

Now that the pilot app is finished, what's next?

MICHAEL: During the next six months to a year, we’ll be making sure the neonate pilot works really well. Everyone who's seen it loves it, so now I need experts in the field to test it. I would think that within the next one to two years, we could extend what we have and do a full-term baby to an infant — so newborn to six months — then in the next three to five years, go for a full pediatric patient. The branches of this product are monstrous — there's safety and education, simulation, root cause analysis, and then there's the international aspect. A neonatal intensivist can train midwives in Burma how to safely resuscitate a baby without having to go there. If we can get them a $15,000 suitcase, they now have a simulation suite connected to a remote expert for guidance.

You go into pediatric medicine because you want to improve the outcomes for children, pure and simple. If you're a kid, the trajectory of your life gets better and better as you grow up, but if some horrible incident happens, that's massive for your lifetime. If you're a neonate, that loss is magnified, because you have a hundred years ahead of you. Your trajectory changes to a week, or a day, or even zero. Even though this product won’t stop poor outcomes, if it can change that trajectory even a little bit, the effect is amplified because of how early you've done it in their life. If we can improve a provider's comfort and ability with resuscitation in any pediatric medicine — from neonates onwards — that’s what it's for. Better outcomes for children across Maine, across the US, and across the world.

Do you have any advice for other innovators in this space?

MICHAEL: I think one thing I learned is that you will get an awful lot of "No" before you get a "Yes". If you truly, truly think that this will help, but the first three people tell you it's not going to work, keep asking around and until you find someone who agrees with you and then work with them and see if you can find more. At first I couldn't even get anyone to really give me an idea if this was even a doable product. Then, “Yes, okay it's possible but then it's gonna cost money” so, then I had to go to people who could get me money and explain to them why I thought it was a doable product.

But now that I've got a prototype, there’s a domino effect — people are like, "How can we help?" or, "When can I buy this?" Another bit of advice is to find someone who is an expert in that field already. I knew that the Interactive Commons at Case Western Reserve had HoloAnatomy, and I don't know why you weren’t the first people I called. Honestly, I thought you guys were too big. You’ve made something so big already, why would you speak to some pediatric intensive in Portland, Maine? But sometimes you’ve got to ask bigger than you think you need to.

HOLOBABY™ PRESS

HoloBaby™ Software Featured by Children’s Miracle Network Hospitals

July 31, 2023 | By Kara Jacques “ZIP code should not determine outcome.” – Dr. Michael Ferguson, Pediatric Critical Care ‘HoloBaby’...